Savennières Roche aux Moines – identity crisis or evolution?

Roches aux Moines

A visit in August to Savennières Roche aux Moines, which is to become an Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée/Protegée in its own right from the 2011 vintage, revealed what might be interpreted as something of an identity crisis, with some quite dramatic shifts in philosophy.

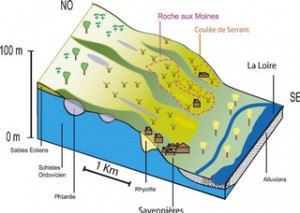

Savennières is a tiny appellation just to the south of Angers on the right bank of the river Loire. It has just 145 hectares, including the 33 hectares of schistous Roches aux Moines (17ha planted), and the seven hectares of equally schistous Coulée de Serrant, solely owned by biodynamic supremo Nicolas Joly. This also becomes an AOP in its own right.

Such ambitious niche production is a long way from the nadir of the 1970s, when Savennières looked to be in near-terminal decline. It emerged from this low point as the Loire’s champion appellation of pristine, dry chenin blanc, where the traditional interpretation meant no malolactic fermentation (malo) and no overt new oak expression.

Over the past half a generation the use of malo and new small wood have evaporated all ideas of a single, unifying style from Savennières. And the seven active producers of Roches aux Moines look set to pursue further experimentation in their new appellation, where using a proportion of botrytised (nobly rotten) fruit and/or leaving a few grams of residual sugar further complicate the evolving picture.

New oak is used in varying proportions with varying degrees of overtness in the wines and without too much apparent controversy among growers. Indeed it is largely the norm among top producers. Views on malo appear more divergent. At Domaine aux Moines there is a laissez faire approach. Proprietor Tessa Laroche said “we do nothing, so it might or might not go through malo. If the pH is 2.8, then there is no malo. We press then do nothing. We use natural yeast. After fermentation we don’t add sulphur dioxide. But we do adapt the vinification according to the taste, so we taste all the time.”

On the other hand, the winemaker at Domaine FL said “I don’t think malo is a good thing. Malo is a marketing and economic move. Not to have malo gives length and something crystalline. It’s better not to have malo for the life of a wine.”

Source: http://www.vinsdeloire.fr/SiteGP/FR/Appellation/Appellation/Savennieres

Are market fads really driving such changes? Some of these growers explained that they’re trying to minimise their use of sulphur as well as working more organically. But when you’re told that malolactic fermentation helps reduce the gap, during bottle ageing, between primary fruit and more developed characters, thus allowing the wine to be drunk sooner, and allowing less sulphur dioxide to be used, one wonders what are the motivations for such noticeable style changes. Does a drive to use less sulphur mean malo is inevitable in order to stabilise the wine? Malo certainly changes the fruit profile and acid balance, two of the recent historic defining parameters of Loire chenin blanc. But it makes the wines more approachable, younger – better for the market.

Charles Sydney, a broker based in the Loire believes the real issue in Savennières is ripeness. He said “all good chenin producers in the Loire pick by hand in selective tris. A harvest with no rot is very unlikely to be ripe. Given chenin’s tendency to be acidic, it is essential to wait ‘til the grape reaches full phenolic maturity before harvesting – bringing sugar and acid into balance but, as important, also bringing the tannins to ripeness, reducing astringency.”

Perhaps such overt changes are more to do with carving out a unique identity for the new appellation. Roche aux Moines means ‘rocks of the monks’. Its “south-east to south-west aspect”, just 75m above sea level, said Damien Laureau, of his eponymous domaine, mean the slopes “are very well exposed.” It’s windy on those outcrops, which reduces the mould risk. And, we are told, the volcanic schist gives a typical bitter quality to the wine.

At some straitened point in history the Roches aux Moines land had been given to the abbey in nearby Angers in lieu of taxes. Domaine aux Moines became a second residence of the monks, and home for those who managed the vineyards, which had originally been planted by Cistercian monks in the 12th century.

With so few growers in the new Roches aux Moines appellation, agreeing appellation regulations may be less fraught than where larger numbers have vested interests. Most growers are already farming organically, biodynamically or in conversion to one of these production systems, so it is no surprise that in the new appellation, no chemical herbicides are allowed.

The growers have also decided that vines should be five years old before they can be used for the appellation, and wines must be bottled at the domaine, though only one producer’s domaine is actually located in the appellation. Yield maxima in both new AOPs will be 30hl/ha versus the 50hl/ha allowed in ‘straight’ Savennières.

As to style, as with many things, it comes to preference. Do you prefer a fatter, creamy pseudo-Burgundy style chenin blanc, or one with racier, more pristine, crystalline lines? On the basis of my brief visit, it seems a small proportion of new oak is both undetectable and even enhancing of the latter style. But malo seems to invoke quite a personality change for chenin blanc.

Savennières Roches aux Moines producers

Domaine Clément Barraut

Domaine Damien Laureau

Domaine aux Moines

Château Pierre Bise

Domaine FL

Domaine des Forges

Château de la Roche aux Moines

Clos Ferrard – Eric Morgat (with a parcel in Roches aux Moines, not yet producing)

My research visit to the Loire in August 2011 was sponsored by InterLoire.