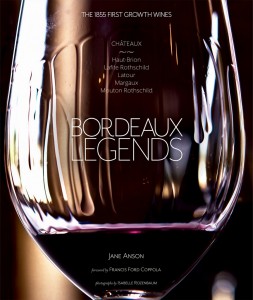

Bordeaux Legends – the 1855 first growth wines, by Jane Anson

| Title of book: | Bordeaux Legends – the 1855 first growth wines |

| Author: | Jane Anson |

| Publisher: | Editions de la Martinière / Stewart, Tabori and Chang |

| Publication date: | 2012 |

| ISBN | 978-1-61769-035-8 |

| Pages: | 285 |

| Price: | US$55 / £35 |

I so want to imagine that copious amounts of tasting the first growths was a vital and necessary part of the research for this book. Perhaps not, but in a sense that replicates opening a bottle of wine and smelling the contents, this book arrived plastic-wrapped so you get the full force of that exciting, anticipatory, new-book aroma once the book is released from its slight transparent cover.

I so want to imagine that copious amounts of tasting the first growths was a vital and necessary part of the research for this book. Perhaps not, but in a sense that replicates opening a bottle of wine and smelling the contents, this book arrived plastic-wrapped so you get the full force of that exciting, anticipatory, new-book aroma once the book is released from its slight transparent cover.

You can’t have a book offering the story of luxury that comprises Bordeaux’s first growths without some evocative photography, and the book doesn’t disappoint in this regard, mixing vineyard shots, with people past and present, as well as artistic shots and archive documents.

The book is not organised in five chapters, one for each of the first growths. Instead, after having introduced the rise of Mouton Rothschild to first growth status, the book charts their collective growth from early reputation building through the 1855 classification and how the properties have solidified their positions on the world stage as the epitome of and aspiration for top flight red wine production from cabernet sauvignon, merlot et al. It explores the links between the five that bond them and define them, and why nearby properties with somewhat similar soils, and similar motivation, have not replicated their elevated and adulated status.

We learn these five properties have been around among the longest, since the fifteenth century or before; they’ve been run and owned by the wealthy, which brings its own powerful family longevity, and they’ve had the time to prove themselves. By the early 1700s, the original four were bought by name in London at sometimes quadruple the price of other Médoc wines. We learn that the wines of Mouton started to earn its stripes in the second decade of the 1700s, and that the French Revolution relieved three of the five châteaux of their wealthy owners.

The author develops the theme of the political and intellectual classes aligning to consume these clarets in destination markets, which at that time was London, thus helping to build their reputation. Not even the Methuen Treaty of 1703, which zero-rated tax on Portuguese wine, dimmed the appreciation for luxury Bordeaux wine.

Into the 20th century and the author charts the changing market focus for the business-canny top flight Bordeaux properties, switching to where high-end demand was thriving – to the USA after prohibition, to Asia in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, and again to the Far East in the late 21st century noughties.

The book sews in the aspiration of Mouton to make the ‘famous five’ from its earliest sources, including that of the property achieving price parity with Lafite as early as its 1851 vintage. The other four châteaux were long already thought of together as first growths. Mouton’s case is also explored in more detail in the chapter on the 1855 classification.

This is a thoroughly-researched and enjoyably readable book (with some lovely asides in parentheses), and one which weaves the histories of the five first growths together through their shared centuries.

Terroir is finally explored in the latter third of the book, with a simple summary of what the ‘firsts’ have in pedological common amid their “very different soils types” (I’ll let you read it for yourselves).

This is a beautifully portrayed book that adds something fresh to the wealth of work already existing about Bordeaux. Bordeaux-believers will undoubtedly love it.